Article

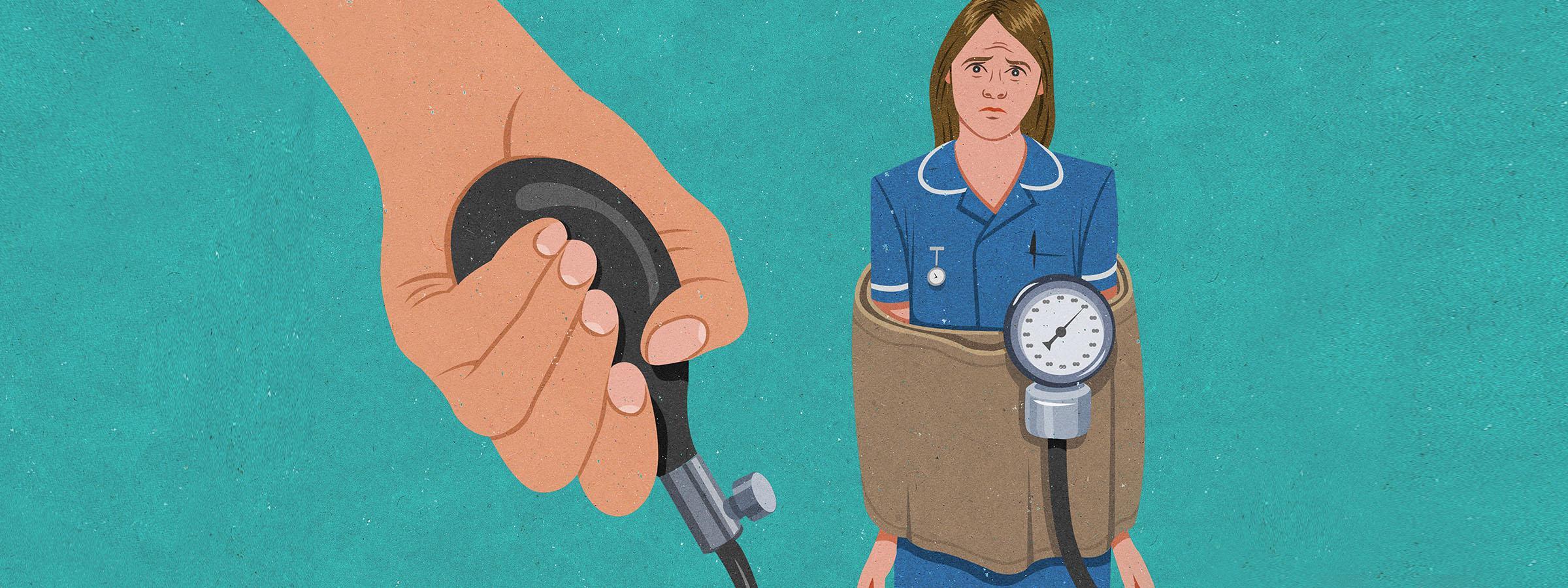

When blame is lopsided, it can lead to tragedy

By Paul Levy | July 18, 2017

So we probably shouldn't be surprised that doctor-driven healthcare systems would find a way to blame nurses for many of the errors that occur. Add to the power imbalance the fact that nurses spend much more time than doctors caring for patients, and so the probability that harm will occur to patients during their watch is statistically higher. Those dynamics often lead nurses to be blamed even when the cause of the harm is systemic, rather than personal.

There are institutions in which the roles of nurses and doctors are seamless, where collaboration and mutual respect rule the day. In these settings, the clinical team retains a hierarchy of authority, but the manner in which work is organized reflects a more egalitarian and collaborative approach. Doctors and nurses are able learn together, enhance care delivery, and minimize the harm that arises from systemic causes.

I keep hoping for the day when more hospitals and health systems will display the latter characteristics, but I see slow progress.

Some recent examples

In the United Kingdom, a nurse named Jane Frances Kendall recently received a 24-month disciplinary period for a 2014 incident in which she failed to attempt CPR on a nursing home resident whom she found to be “waxy, yellow and almost cold," with no pulse or vital signs. Britain's Nursing and Midwife Council ruled that Kendall was acting outside of her competence and was not qualified to certify death.

But one commenter on the report, a former executive nurse in Britain's National Health Service, noted that the review panel didn't appear to understand the difference between diagnosing death (a clinical job) and certifying death (a legal responsibility). “Nurses can't and don't need to certify death," she wrote, “but they can diagnose death and act in accordance with best practice guidance."

A disciplinary action can have a huge effect on a nurse's career.

At MedStar Health in 2011, a nurse named Annie administered insulin to a patient whose glucometer read “high," and who reported that her blood sugar felt high. In fact, the patient's blood sugar was critically low, and she was admitted to the ICU. Annie was suspended, but an internal review later determined that the equipment was at fault, and her suspension was reversed.

In a 2014 MedStar training video about the incident, promoting a systems approach to safety culture, Annie talked about how the experience affected her psyche: “I felt like I was talked to like a five-year-old. I wasn't talked to like I was an adult. I mean, I'm a nurse because I come to take care of people. For a long time, it really shook me. When I came to work, I was apprehensive about everything I was doing."

We could understand why a person who is unjustly blamed for a medical error might be more likely to commit another one than his or her colleagues. But it's just as likely that, because there is a spotlight on their performance, there's a greater tendency to misinterpret their actions as individual weakness than as a function of the environment in which they work.

Indeed, the root cause of many medical errors is a lack of proper systems and protections in the workplace. In 2012, NBC News reported on a nurse who accidentally disposed of a living donor's kidney during a transplant, not realizing that it was in a chilled, protective slush that she removed from an operating room. The hospital eventually blamed poor oversight and communication and insufficient policies, and disciplined both nurses and physicians. But the punishment doled out to the nurses was more severe than to the doctors.

When the blame is lopsided, it can lead to tragedy.

In 2010, Kimberly Hiatt, a NICU nurse at Seattle Children's Hospital, was fired after a medication error that led to an infant's death, and later committed suicide. But a few months earlier, a dentist at the same hospital hadn't been fired for prescribing an incorrect dose of a Fentanyl patch to an autistic 15-year-old boy after routine dental surgery, leading to his death. And an ER doctor wasn't disciplined for wrongly administering a drug to a critically ill patient through an IV instead of an injection in the muscle, leading to complications.

In a letter to the editor to The Seattle Times after Hiatt's suicide, retired anesthesiologist F. Norman Hamilton, M.D., noted the injustice: “The fact that the hospital changed its policies after the death implies that they realized that its policies were inadequate. Despite this, the hospital decided to fire the nurse for an arithmetic error … If we fire every person in medicine who makes an error, we will soon have no providers."

The power to reverse this phenomenon lies with hospital leadership. Absent affirmative actions to protect nurses from premature and inappropriate blame, they will remain at professional and personal risk from a doctor-dominated setting when patients are harmed.

Human factors expert Terry Fairbanks, M.D., has explained to me that this is one of the biggest barriers to moving organizations to an overall safer and more resilient level: “We stop with individual blame, which makes leaders blind to the work-flow and process set-ups, which are really what need to be managed."

At the personal level, we owe it to the nurses and their profession to address this problem. At the health system level, we owe the same to our patients if we are to create a safe and high quality patient care environment.

The blame mentality when errors occur is just one symptom of out-of-whack power structures.

The blame mentality when errors occur is just one symptom of out-of-whack power structures.

But the leadership imperative goes beyond the response to medical errors. Indeed, the blame mentality when errors occur is just one symptom of out-of-whack power structures. At the clinical departmental level, there can be a tendency to diminish the role of nurses in morbidity and mortality case reviews or root cause analyses. Why? Because nurses often observe things that are viewed as undermining doctors' authority or judgment. The arrogance that can accompany doctors' higher degree of training acts to exclude what are often astute observations.

The hospitals and nursing homes that offer the highest levels of care are the ones in which concepts of shared governance, crew resource management, joint training and like are built into the everyday lives of doctors and nurses. But the unbalance often starts at the highest level of governance, where boards of trustees have staff doctor representation but less or no staff nurse representation.

I have seen proposals to add the nursing view to boards dismissed with the contention that nurse board members will only advocate for higher salaries and different staffing ratios. In contrast, no one seems to believe doctor board members will behave in a parallel selfish manner. No, they are viewed as paragons of virtue, without whose judgment a board cannot possibly understand the complexities of care delivery.

In short, unless governing bodies and leaders accept the premise that doctors and nurses are both among the most well-intentioned people in society and grant them equal status in the overall and clinical governance of health care institutions, we inevitably build in a skewed power structure that undermines our ability to provide the best care.

Paul F. Levy is the former CEO of Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center and the author of “Goal Play! Leadership Lessons from the Soccer Field." Artwork by John Holcroft | Getty Images